Personal Reflections

The Public Life of the People of God

Reflections on Scripture, Theology and Ministry in a Time of Crisis

You may download any of the Coronavirus material in this collection for personal or ministry use. Please do not duplicate or distribute without permission and attribution. Thank you.

-

Good News in a Time of CoronavirusReflections on 1 Corinthians 15

-

Las Buenas Nuevas y la Coronavirus1 Corintios 15

-

Inspired by the Laments in the Psalms, written for the Shipibo-Conibo indigenous people group in Peru's Amazon

-

Un Lamento AmazónicoAmazon Lament in Spanish

-

A theological reflection on the coronavirus for the RAP - Spanish acronym for Perú Amazon Network - a network of evangelical mission organizations working primarily with indigenous people groups in Perú's Amazon basin.

-

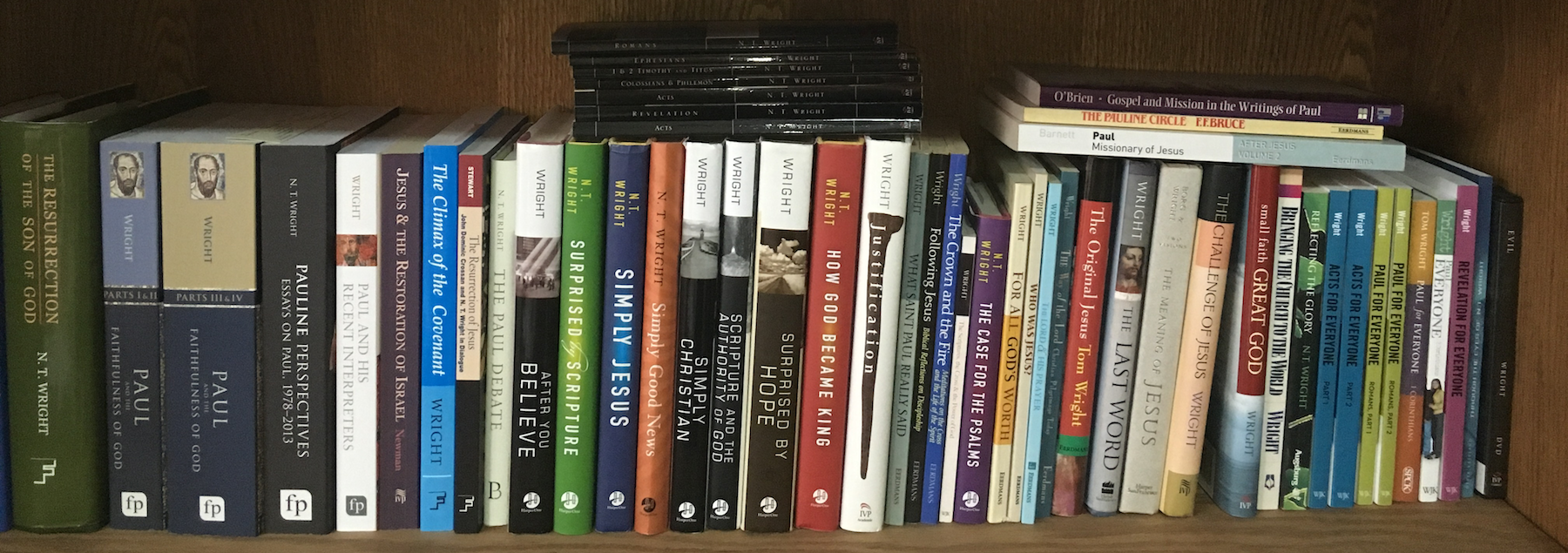

An article by prominent evangelical New Testament theologian N.T. Wright, surprisingly titled "Christianity Offers No Answers About the Coronavirus. It's Not Supposed To". Published in TIME magazine; used by permission.

-

El mismo artículo, traducido por el miembro del equipo al español.

-

El mismo artículo, traducido por David Shapiama, pastor de la Iglesia Evangélica Misionera de Pucallpa, al español.

Elijah & the Sound of Silence

-

Background and Notes for "Elijah and the Sound of Silence" presentation. (PDF)

-

Slide presentation of 1 Kings 19:9b-18. (Apple Keynote)

-

Slide presentation of 1 Kings 19:9b-18 (PDF)

"Why should we give of our hard-earned income to the work of global missions? We have families to feed, neighbors to care for, churches to support, local ministries to the poor and marginalized in our own communities."

The answer is as straight-forward as the questions are understandable. We are to give to one-another, and to others far-away whose names are unknown, whose faces we will never see, because self-giving, reaching beyond ourselves with the resources we steward, is the very nature of the God known by Christians as Father, Son and Holy Spirit, the Creator God. He created us in his own image; being created in his image entails that we are, by nature, givers.

"Who is the Living God?" "What does God have to do with our acts of giving?"

These are the sorts of questions we ask, questions that are straight-forwardly answered in a personally and theologically reflective article by J. Scott Horrell, professor of Systematic Theology at Dallas Theological Seminary. Horrell's writing is both profoundly biblical and personally challenging; I return to re-read and reflect on it again and again.

The author, in his words, addresses three points: "1. The self-giving nature of the tri-personal God [the Christian belief in the Trinitarian God]. 2. The implications of a self-giving God for man as [human beings created in] the image of God. 3. How understanding the self-giving God should affect our concept of the local church and its role in the world." My reflections bear especially on the first two points as they bear on our giving to missions generally, and our RiverWind mission in the jungle of Peru specifically.

Horrell summarizes Christian belief in the Trinity, our encounter in Scripture with "a Father, Son and Holy Spirit each loving the other, giving to the other, honoring the other, glorifying the other...profoundly and infinitely self-giving." He then unpacks what this means for us to be human, created in the image of God: "...it is not in 'finding ourselves' that we discover what it means to be human. Scripture repeatedly points us to our Creator, the living God. When we focus upon him– looking upward not inward–then we begin to recover our humanity." Quoting Karl Barth: "...our definition of person must be finally situated in God himself'."

This is summarized, Horrell notes, in the greatest commandments affirmed by Jesus: "...love the Lord our God with all our heart, soul, mind and strength and... love our neighbor as ourself (Mark 12:29-33)." Finally he quotes Cuban evangelist B.G. Lavastida: "There are three paradoxes of the Christian life. You must give in order to receive, you must let go in order to possess, and you must die in order to live."

In short, because God is by nature self-giving, and if we are created in God's image, then we are by nature, as humans, a giving people. When we live as givers, we live like God. Download and read more, from Dr. Scott Horrell… [used by permission]

for Elizabeth - July 8, 2019

-

Reflections on Psalm 18; for Elizabeth - Ruth's mother, in the hospital critically ill following surgery.

The Self-Giving God & Giving to God's Global Mission

Mission & Collision

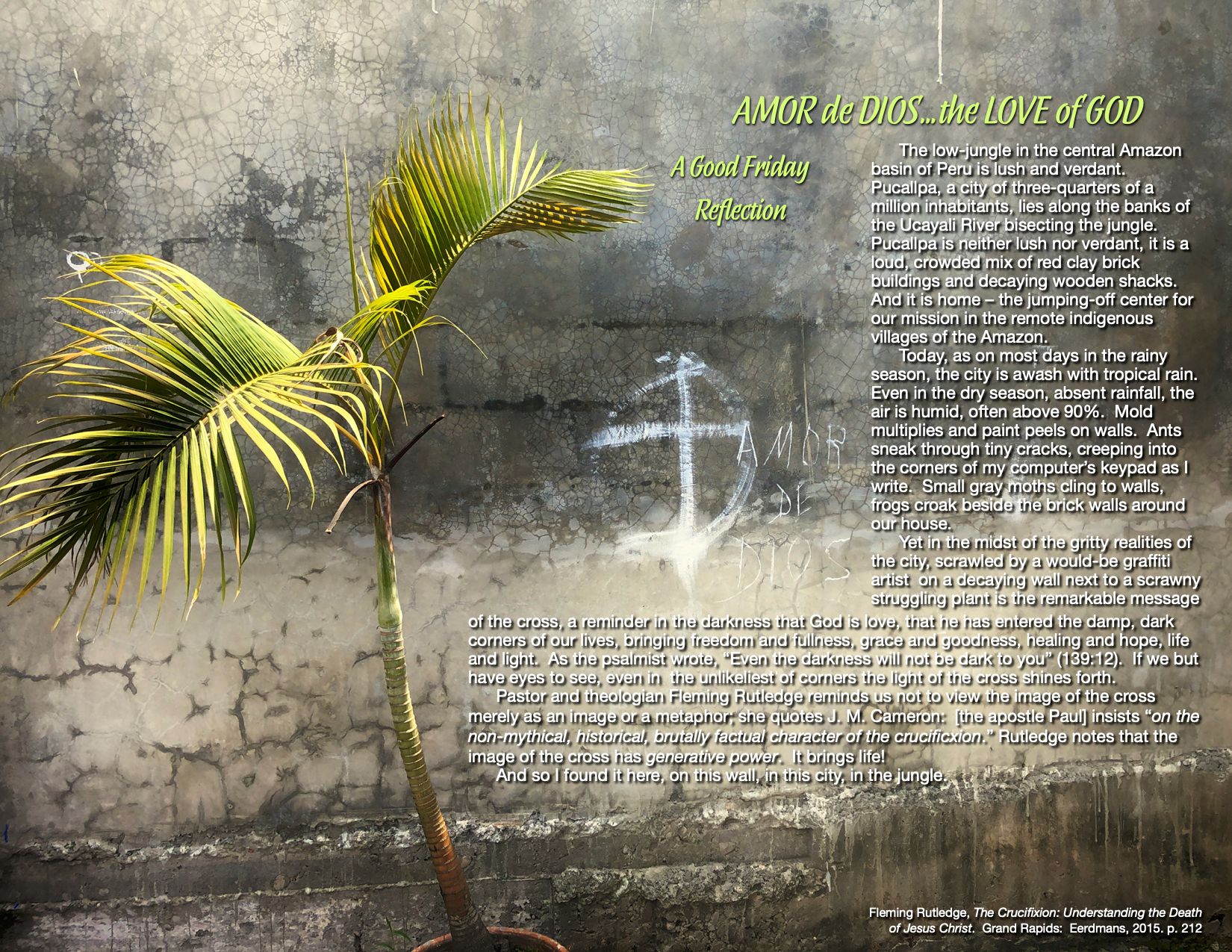

When we are upriver in the jungle, the community of Nuevo Italia has limited electrical power, on from dusk till 9:00pm. In the black darkness that follows the stars above the southern hemisphere shine like diamonds.

The church at Antioch was the springboard of the ancient divine charge given to Abram to be - through his immediate descendants, Israel - the father of a people more numerous than those bright stars above the Near Eastern skies. Abraham was charged to be a blessing to all nations on earth (Genesis 15:5; see also 12:2-3, 17:4-6 and 22:15-18.

Following the commissioning of Paul and Barnabas by the Antioch church, these two answered their Jewish antagonists in Pisidian Antioch, quoting Isaiah’s words about Israel’s covenant; it was not enough simply to be God’s chosen people, he chose Israel, as he chose Paul and Barnabas in the first century, as he chooses us in the 21st century, to be 'a light to the Gentiles, bringing salvation to the ends of the earth’ (Acts 14:47, quoting Isaiah 49:6).

Kavin Rowe – in his careful study of Paul’s encounters with pagan cultures and Roman power, World Upside Down – shows through detailed exegesis how, in all of the cities on this, their first missionary journey (Acts 14), subsequently in Philippi (Acts 16), Athens (Acts 17), and Ephesus (Acts 19), the gospel of the risen and exalted Jesus collided with paganism and confronted imperialism. “In Acts, it is either magic or Christianity, either Artemis or Christ” (World Upside Down, p. 49). “This collision… [between the life-shape of Christianity in the Graeco-Roman world and the larger pattern of pagan religiousness]”, he continues, “rests ultimately in the theological affirmation of the break between God and the cosmos. For to affirm that God ‘has created heaven and earth’ is, in Luke’s narrative, simultaneously to name the entire complex of pagan religiousness as idolatry and, thus, to assign to such religiousness the character of ignorance. Pagan religion, regardless of the specific differences engendered by time and locale, knows only the cosmos; it does not know God" (p. 50).

The collision of Christianity with paganism inevitably in Paul’s day – as it will also in ours – brought confrontation with Roman imperial authority, which - in the final analysis - it will always do. The outcome in Acts between the missionary Paul and the Roman authorities was not – as Rowe's exegesis of Acts demonstrates – as is often thought a simple rapprochement between religion and political power; “the Christian mission…is not a counter-state. It does not…seek to replace Rome, or to ‘take back’ Palestine, Asia or Achaia” (p. 87). At the same time, he reminds us, “following Luke’s narrative is to read Christianity not as a call for insurrection but as a testimony to the reality of the resurrection.…[yet] the rejection of insurrection does not simultaneously entail an endorsement of the present world order…” (p. 88).

Here in Peru, as in the United States, this is election season. Christians are citizens of national political systems, but we are first and foremost citizens of the Kingdom of God, where the incarnate Jesus, crucified under the power of the state was raised by the power of God, and declared to be both Lord and Christ - the expected messiah, the King for whom the Jews were waiting. In Paul’s day there existed not only the pagan religions, their followers subservient to the gods, but an imperial cult which declared that Caesar, the Roman king, was thought and thought himself to be god or lord. Culture, religion and politics all walked hand-in-hand. The resurrection of Jesus and his exaltation reminds us that he is both Lord and King. It should give us pause, both in our missiology and in our doxology.